I recently served in a jury where we were asked to decide on a landlord-tenant case in a civil trial. Aside from the fact that it was clear no one wanted to be there (myself included), I actually learned quite a bit about the importance of a trial by jury even in a small claims court case like this one.

Perhaps from a more selfish standpoint, since I am also a landlord, I actually saw this as an opportunity to learn a bit more about landlord and tenant disputes that end up making it to a trial by jury.

The bottom line was that I definitely learned in a rather indirect way (by being forced to perform my civic duty) that it’s in everyone’s best interest to perform preventative measures to ensure you don’t get irreconcilable disputes that end up being mediated by total strangers in court.

Having been both a tenant as well as a landlord, I can now see how both parties must fully understand and agree to the terms of the relationship. Failure to establish this understanding can and will ultimately result in messy situations that require the intervention of our justice system.

Indeed, that was certainly a homeowner headache for both parties in the case that I was on, which I’m about to describe. Keep in mind that this was merely one example of how a misunderstanding can blow up into a court case, but after reading this article, I hope it’s clear that there can be any number of other ways landlord-tenant disputes can make it into court, but it’s all preventable!

What Was The Case About?

This was a trial concerning a dispute between the landlord and the tenant regarding what the monthly rental rate was.

The unit was within a multi-unit property in Monrovia that contained three bedrooms.

The landlord claims that the rental amount was for $2100 per month while the defendant claims that the rental amount was for $1500 per month.

For the sake of simplifying the math, I’ve chosen these values instead of using the actual amounts.

What muddied the waters about this particular case was that the rental amounts were said to be verbally agreed to so this was a classic case of he said she said.

I won’t get into re-hashing the particulars of the trial because it consisted of a lot of waiting, about 90 minutes of jury selection, about 3 hours of testimony and cross-examination, and maybe 30-60 minutes of juror deliberation and verdict.

The jurors were instructed to treat the actual exhibits as evidence for the arguments, but the oral testimony and cross-examination should not be treated as evidence though they may sway opinion on the matter.

When all was said and done, the case proceedings could be summarized as follows:

- Plaintiff asked for unpaid rent and unpaid difference of disputed month or $9000

- 4 months unpaid * $2100/month + $600 unpaid for disputed month

- Defendant seeking to only pay at the amount of $1500 per month

- Burden of proof was on plaintiff

- The plaintiff had an attorney while the defendant represented herself

- 4 witnesses were called to the stand for cross-examination

- one was the defendant

- one was the plaintiff

- one was the process server

- one was a neighbor who helped the defendant move in

- The evidence presented to the jurors consisted of:

- Rental checks paid from the start of occupancy to the time rent stopped being paid (a period of about 7 months)

- The first two checks were for $1500

- The next 2 checks were for $600 (paid within the same month)

- The next 5 checks were for $2100

- A process server notifying tenant of intent to pay $600 or quit within 3 days

- Another process server notifying tenant of the deadline elapsing several days later

- Rental checks paid from the start of occupancy to the time rent stopped being paid (a period of about 7 months)

- The rest of the trial was verbal testimony

- It was understood that rent was not paid for 4 months

- Rent for the disputed month was paid, but it was only for $1500 and not $2100

- The trial took place about 5 months after the process papers were first served

The plaintiff pretty much kept their argument simple in that there was rent to be paid, and there was an amount unpaid that was owed. They also tried to establish that the rates were deeply discounted from the market rate for that area (i.e. a “friend’s rate”).

The defendant tried to establish that she had been paying (her understanding) of rent on time and that she tried to establish that she was a “good tenant”. She also tried to discredit the process server with her own witness she called to the stand while also trying to establish that she was out of town at the time the process papers were served.

What Was The Result Of The Case?

The judge established the ground rule that in this civil case, we only needed a 9/12 majority to reach a verdict.

The jury was asked to answer 5 questions:

- Question 1: Was the plaintiff the landlord?

- Question 2: Was the plaintiff owed rent?

- Question 3: Was the defendant properly notified of deficient amount of rent?

- Question 4: Did the defendant fail to pay the amount owed as stated by the due date?

- Question 5: What is the damage amount?

Questions 1-4 were yes/no questions, but we were also asked to come up with a damage amount for question 5.

The results of our deliberation were as follows:

- Question 1: Jury voted 12/12 yes

- Question 2: Jury voted 11/12 yes

- Question 3: Jury voted 11/12 yes

- Question 4: Jury voted 11/12 yes

- Question 5: This one requires an explanation

- The plaintiff suggested $9000 as the damage amount, and the jury voted 8/12 yes on this figure

- Since this wasn’t the required majority, an alternate damage amount for $6400 ($1600/month * 4 months) was proposed

- Jury voted 11/12 on the adjusted amount

So the jury ruled that the defendant owed $6400, which was less than the $9000 they asked for, but more than the $0 that the defendant might not have paid had we totally taken her side. In our minds, this was a fair compromise because the unpaid rent would be for the amount she would have paid anyways.

That said, we only voted on the questions relating to whether the landlord was owed rent and how much, but we were not instructed to do anything further. That said, I hope that there would be a firm understanding going forward of what the rent should be going forward, but that question is out of our hands.

Why Avoid Going To Court?

(image provided by Visitor7, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

One major takeaway I got from this entire process was the rather random and wildcard nature of the whole trial by jury.

This somewhat unpredictable aspect of the court system included the jury selection process as well as the behavior of the individual jurors themselves. Even the rules that the judge set (each of whom could have his or her own rule to reach a verdict in a civil trial) could have been a random process.

For a disagreement to be left to such uncertainty and chance through the court system, that could be too much to bear for either side.

Heck, if you’re a landlord in the state of California, many landlord-tenant disputes that go to court have reportedly been in favor of the tenant. I know our tax accountant questions the wisdom of holding onto a rental due to the amount of leverage the tenants have, especially if the tenant is problematic (e.g. refusing to pay rent, causing damages to the property, etc.).

Moreover, regarding our particular court case, us jurors don’t even know who’s paying the legal fees (e.g. the attorney representing the plaintiff), which I’d imagine wasn’t cheap. We also don’t know if the defendant has to pay the plaintiff’s attorney fees for losing this case.

(image from Dietmar Rabich / Wikimedia Commons / “Würfel — 2021 — 5959” / CC BY-SA 4.0)

So not only were a lot of peoples’ time and money spent doing their civic duty (i.e. an expenditure of public resources) to try to resolve this case, there’s also time and money spent in gathering evidence and coming up with an argument. I’m sure the mental energy devoted by either party couldn’t have been a pleasant experience. Even the defendant broke down in tears when she gave her closing arguments.

In our particular court case, we had one juror who completely took the defendant’s side (though his position wasn’t based on the evidence provided; only on verbal testimony on the defendant’s side). What if we had at least three more jurors who held a similar position (something the defendant maybe could have been more shrewd about which jurors to dismiss; an example of how the current legal system could be manipulated by the interested parties)?

That could have easily resulted in a much longer deliberation or even a hung jury let alone a completely different outcome in the case.

Indeed, there’s so many what-ifs that could sway the fate of the plaintiff as well as the defendant one way or the other. Such decisions, which could alter someone’s life for better or for worse, being left to chance is a risk I’d argue is not worth taking in the vast majority of cases.

How Could This Whole Issue Have Been Prevented?

If going to court is such a stressful and uncertain affair, it’s natural to ask what could have been done to prevent the whole ordeal in the first place in this particular case?

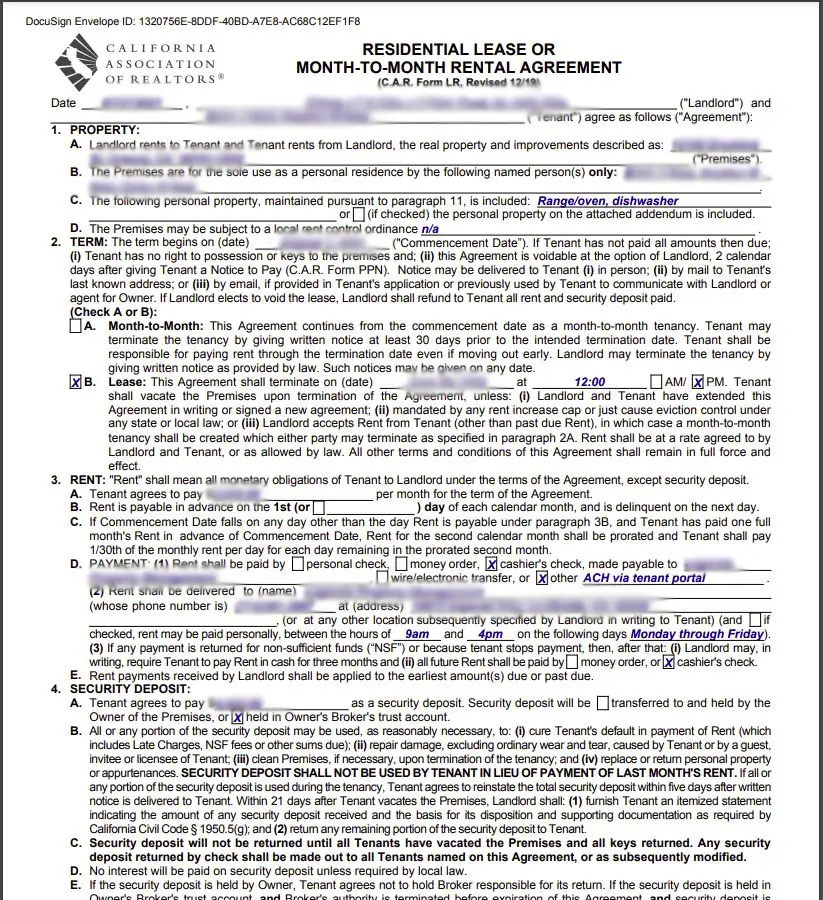

Well, the most obvious thing was to first have everything in writing, especially the all-important rental agreement, which establishes the relationship between landlord and tenant. This written agreement should spell out all aspects of this relationship in an unambiguous manner.

Having such records minimizes the chances of hearsay (i.e. he-said-she-said), which is not to be treated as evidence in court should it come to that. In fact, even when you’re negotiating an out-of-court settlement, it helps to have written records to facilitate the negotiations due to a reduction in the chances of misunderstandings.

That said, having written records should also extend to other aspects of the rental relationship such as having records for every communications (including but not limited to service/repair calls, questions/concerns, moneys exchanged, etc.).

Based on the jury experience, we were instructed to rule based on the evidence provided.

However, if the evidence was as scarce as a handful of voided rent checks and some process server paperwork, there was not enough evidence to establish things like:

- rental amount (the main reason why the plaintiff didn’t get what he asked for)

- whether the rental was purely informal charity between friends (something the defendant wasn’t successful establishing due to no hard proof of this)

- whether the tenant was a “good tenant” or not (something that’s hard to prove though some paperwork like records of open and honest communication to corroborate this could have helped if such evidence was available)

Now if the landlord would rather do all this recordkeeping by oneself, that person would have to be very organized, have some storage space for the recordkeeping as well as an index to recall everything quickly and efficiently, and devote a lot of time and money for this infrastructure and standard operating procedure (SOP).

My wife and I had discussions about this when we first decided to rent out the home we had lived in for 10 years, and that was when we ultimately decided to go with a property manager.

Ever since we’ve done this, we can’t imagine not doing this, and there have been repeated instances where having a property manager (who’s in the business of doing this full-time) made things go smoothly. This court case was yet another example of where having such a resource would have allowed us to go about our lives without devoting too much of it to real estate and/or landlord-tenant matters.

I’ve written an in-depth article about the benefits of hiring a property manager from our own experiences as that’s a whole topic on its own.

Conclusion

This was a cautionary tale of the pitfalls of verbal agreements even if you’re doing a favor for a friend or relative. I wonder if the friendship between the plaintiff and defendant has now been forever tarnished after this experience.

Indeed, we’ve seen the random nature of a trial by jury as well as the importance of having written evidence regardless of whether you’re in a court case, you’re settling out of court, or you’re seeking to prevent major problems from arising in the first place!

Having written agreements should not be considered as a way to screw someone else over by hiding behind legalese. It’s supposed to protect both the tenant and the landlord for misunderstandings so the rental relationship can be as smooth and contention-free as possible.

In fact, even if you’re doing a favor for a friend or relative through a landlord-tenant relationship, it would be very wise to establish the business side of the relationship and not mix the personal aspects of the relationship, and that’s why we have written contracts!

On a personal note, serving this court case was not as bad as I had thought (as I had dreaded going to downtown Los Angeles due to traffic), and I learned quite a bit about the court process as well as one example of a landlord-tenant relationship that went bad.

Thanks to the public transportation option, I even had an opportunity to appreciate downtown Los Angeles during the lunch break, which was something I never really got to appreciate as a driver due to the traffic and parking situation.

Sometimes you have to make lemonade out of lemons, and in this particular instance, I felt like I got a bit more out of the experience as opposed to others that tried to find ways to weasel out of their civic duty. Of course, I did have the ulterior motive of wanting to learn more about someone else’s homeowner headache.

Just don’t make the same mistake as the plaintiff did by not having a rental agreement in writing.